This paper explores the complexities of managing leg ulceration in a prison environment and the issues associated with the implementation of a wound strategy. The wound strategy was developed following an internal audit, which highlighted inefficiencies in the current provision of leg ulcer assessment and management.

As of June 2023, the UK had a total prison population of approximately 95,526 people comprising:

- 85,851 in England and Wales

- 7775 in Scotland

- 1900 in Northern Ireland (Sturge, 2023).

The Ministry of Justice (2023a) stated the UK prison population consisted of 86,498 male prisoners, 3429 female prisoners and 2079 on home detention curfew (people released early from custody providing they have a suitable address to go to, often called tagging). The population is forecast to increase to 98,700 by 2026 (House of Commons Library, 2022). Healthcare provision is a challenge due to over arching security concerns and challenges associated with the recruitment and retention of registered practitioners. NHS England (2019) in the long-term plan, attempted to address inequalities between people in prison and the general population, but strict prison regimes often make translation of NHS services in these environments difficult. The Royal College of General Practitioners (2018) recognised difficulties in providing healthcare in secure settings, arguing that the aim was not to provide the same services as those in the community, but that equivalence should reflect the need for healthcare in prison to be ‘at least’ consistent in range and quality with that is available in the community. Healthcare workers in secure settings continue to strive to deliver equivalent services to those available in the wider community.

Patients in custody are a uniquely vulnerable population with a disproportionately high burden of disease and an increased mortality rate compared with the wider UK population. The Nuffield Trust (2020) reported that the proportion of people in prison aged over 50 increased from 7% in 2002 to 17% in March 2020. Given the significant health needs of people in prison, His Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service (HMPPS) uses age 50 to describe ‘old age’ in prisons, with the average age of people dying in prison being 56 compared to 81 in the general population (Sturge, 2020). The Ministry of Justice (2023b) approximated more than one in six people (17%) in prison are aged 50 or over — 14,578 people, with 3824 being in their 60s and a further 1876 people being 70 or older. The number of people in prison aged 50 or over is projected to grow by around 1000–2400 people between 2022 and 2026 (Ministry of Justice, 2022). The prison population is ageing: in 2002, 15% were under the age of 21 compared with 4% in 2023 and the number over the age of 50 went from 7% in 2002 to 17% in 2023:

- Prison sentences have been lengthening, with 56% of determinate prison sentences being over four years compared with 40% in 2013

- Foreign nationals made up 12% of the prison population

- People of minority ethnicities made up 27% of the prison population compared with 13% of the general population (Ministry of Justice, 2022).

Accompanied by a high prevalence of mental health and substance misuse, patients often arrive in prison having had limited access to or engagement with healthcare services in their communities. The Prisons Reform Trust (2023) and the HM Chief Inspector of Prisons (2022) stated that around 2/3 of people in prison, surveyed by inspectors between 1 July 2021 and 31 March 2022, reported having mental health problems. Additionally, there are added complications of poor health, self-neglect and a history of substance abuse, where analgesic options are complex decisions delaying effective pain management and wound healing.

Wound care complexities in prisons

Healthcare staff working in a prison environment require a unique skillset (Jeker et al, 2023), including specialist knowledge in areas such as substance misuse, management of communicable diseases and mental health. They also have to understand physical needs in addition to having effective communication and risk management skills. Teams are relatively small compared with healthcare services outside of a prison, many prison sites deliver 24-hour services in environments where access to external providers is affected by security considerations, and operational capacity to facilitate escorts outside of the prison gates. Difficulty in accessing timely secondary care services can lead to frustration, anxiety and poor engagement, coupled with psychological barriers where patients may feel dehumanised by the requirement to be cuffed to officers when attending appointments, and the stigma attached to this in public spaces.

Physical health in the prison population has been discussed and reported as poorer than in the general population, even before incarceration, with prisoners having had poor health linked to early childhood abuse, neglect, and trauma; problems with housing or employment; and higher rates of smoking, alcohol, or substance misuse (House of Commons, 2018). Leg ulcerations are particularly complex to manage, with multiple causal factors such as an ageing population of prison patients, and a high prevalence of ulcers resulting from intravenous drug use. Staff are recruited from diverse healthcare backgrounds and do not always possess specialist skills and knowledge to initiate care plans.

Prison environment

Within the prison environment there is a need to ensure equity of care for those who require healthcare allowing them access to evidence-based treatment such as strong compression for venous leg ulcers (VLU). Healthcare interventions are delivered in numerous areas including the clinic and cells. Patients reside in small cells, which are difficult to adequately ventilate, cells can be hot and uncomfortable in the summer months, especially in older establishments with double occupancy and a lavatory in the same room. Unlike many healthcare establishments, the environment in custody settings directly impacts a nurse’s clinical decision making when considering treatment pathways for patients with wounds. The high prevalence of mental health conditions in prisons necessitates additional risk assessments to ensure patients are not likely to use bandages as ligatures or ingest dressing materials.

There are challenges for patients to self-care in environments where they have limited control over standards of cleanliness in communal areas. Patients with wounds may not wish to use communal showers, due to highlighting a vulnerability (the wound), which can reduce self-esteem and be perceived by others as a weakness leading to victimisation. The impact of frailty, mental health and physical disorders has been discussed (Ricciardelli et al, 2015) who stated that these could all be equated to vulnerability. Not all establishments are equipped with janitors sinks or sluice facilities, complicating support with leg washing where risk assessments for disposal of water are required. Wound cleansing is an integral component of all wound management (Queiros et al, 2013), however, there is limited evidence regarding the most effective way to clean a wound (Woo, 2018) or which solution is most appropriate for leg ulcer cleansing (McLain et al, 2021). McLain et al (2021) suggest that in the absence of evidence to support the use of cleansing solutions or techniques, clinical care should be informed by current national guidelines, costs, and patients’ preferences. This requires consideration in prisons where there may be limited knowledge of national guidance.

It is vital to consider the safety and wellbeing of clinicians. Patients presenting with wounds in custody settings are incredibly varied. Elements that increase safety risks and may negatively affect consultations include substance misuse and detox regimes. Palfreyman et al (2007) reported that pain and isolation were the main elements affecting quality of life in people who were intravenous drug users, leading to them not accessing health care services due to a fear of discrimination.

Pain associated with leg ulcers has been well documented (Walshe, 1995; Briggs, 2003; Ryan et al, 2003; Leren et al, 2020). Leren et al (2020) reported that up to 80% of people with chronic wounds experience mild-to-moderate pain between dressing changes. Effective pain management can be challenging, as there are strict guidelines for prescribers with medications that have considerable value as commodities within a prison setting. It is important to understand that security requirements are prioritised, and this can sometimes have an impact on care delivery. Local regimes specify exercise and association periods, which often contributes to more sedentary behaviour with a potential negative impact on leg ulcer healing. There are numerous studies reporting the importance of mobility in people who present with chronic venous disease (Abelyan et al, 2018) as the function of the calf muscle is reduced, this is reduced further in those people who also have a VLU (Cetin et al, 2016). The lack of freedom to mobilise outdoors or have sufficient space indoors within a prison setting can lead to further deterioration of chronic venous disease and a slow wound healing.

To try and overcome these challenges, it was agreed that a study of this complex environment would be undertaken. The aim was to determine what support could be developed to help healthcare staff deliver evidence-based leg ulcer interventions and improve health outcomes of prisoners.

Supporting healthcare practitioners to develop wound care knowledge and skills

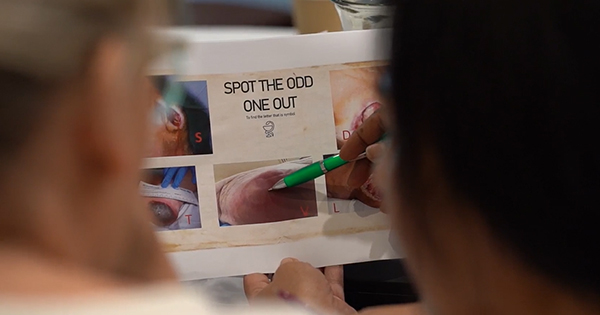

An internal audit identified that staff were not confident managing patients with leg ulcers, highlighting the need for an organisational strategy to support nurses, which included access to training programmes on health promotion and effective communication strategies. It was also noted that a focused wound care strategy for the assessment and management of leg ulcers was required as was a formulary update.

Audit feedback identified that a standardised training programme needed to incorporate:

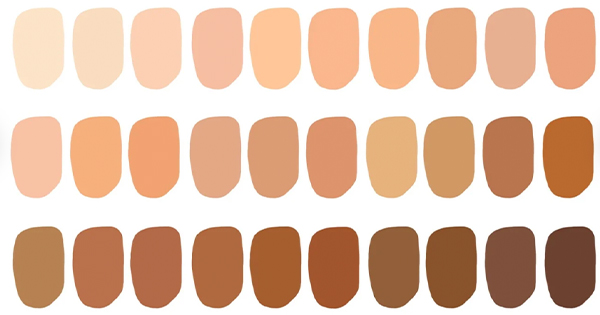

- The importance of assessing patients skin on admission

- Accurate and timely history taking for those with a leg ulcer arriving in custody settings

- Ankle brachial pressure index (ABPI) assessment using a doppler

- Identification of underlying aetiology e.g. venous, mixed arterial/venous disease, arterial disease

- Mobility assessment

- Psychological assessment.

Following a series of workshops and focus groups, a wound care strategy was devised to promote equity of care interventions for people admitted with leg ulceration.

Developing a wound care strategy

The strategy aims to improve access to training, while developing knowledge and skills to ensure safe practice. This should support the cohort of nurses with a specific interest in tissue viability who will transform wound management, and more importantly, enhance timely wound healing for this vulnerable patient population.

The wound care strategy involved a collaboration between the prison wound care team and a small group of experienced primary care/practice nurses who recognised the need for a consistent approach using evidence-based practice and research to inform high-quality care within the constraints of a challenging environment. Compression therapy was an essential element of the strategy as recommended by the National Wound Care Strategy Programme (NWCSP; 2023), however, patients had complained that multiple layer compression was too warm and uncomfortable, leading to many patients removing the compression. To overcome this a range of compression systems were evaluated and evidence supporting each system reviewed. UrgoKTwo multicomponent compression bandage system was chosen as it was supported by robust clinical evidence (Hanna et al, 2008; Tai et al, 2021), was easy to apply ensuring the correct level of compression was applied at the ankle and to the leg. The systems maintained pressure for up to seven days and patients reported it was light and comfortable to wear.

Elements of the new strategy, including comprehensive care planning and adherence to guidelines and evidence-based products, were trialled for approximately six months as an informal evaluation. During this time patients treated with UrgoKTwo compression reported the bandages were comfortable to wear, increasing adherence to wearing the compression system and engagement with treatment plans.

When considering appropriate treatment pathways, nursing staff reported that UrgoKTwo was simple to apply, as well as being easy to teach application for new staff members. Simplicity of application ensured consistent therapeutic levels of compression was achieved.

The final stage of the wound strategy will be updating the existing formulary to align with current local and national guidelines but also to simplify the choice of appropriate products. Currently pathways and guidelines to support product choice are being developed and formats considered that will be tailored to the needs of prison nurses to guide and assist in the clinical decision-making process.

Discussion

The strategy remains a work in progress but during this process a clear focus on raising awareness of wound care guidelines and resources has inspired further interest in this area. In the last year, colleagues have attended wound conferences and networked with industry clinical experts to consider how they can improve wound care and evidence gold standard practice with a patient group that are underrepresented in current research. Working with industry clinical experts has enabled access to training platforms and support, and teams eagerly await the finalised strategy being rolled out nationally. The governance teams are engaged and committed to supporting improving outcomes in wound healing and the positive impact this will have on the patient experience in our services.

Patients in custody settings are not merely prisoners nor passive recipients of services and are entitled to equal access to evidence-based care. Promoting excellence in wound care provides an opportunity to improve the quality of life for vulnerable people, raise awareness of the uniqueness of these patients, their particular needs and ensure inclusion in future research. It exemplifies opportunities in the sector and may elevate the status of our nurses, attracting other skilled professionals who have a passion for quality improvement and innovation