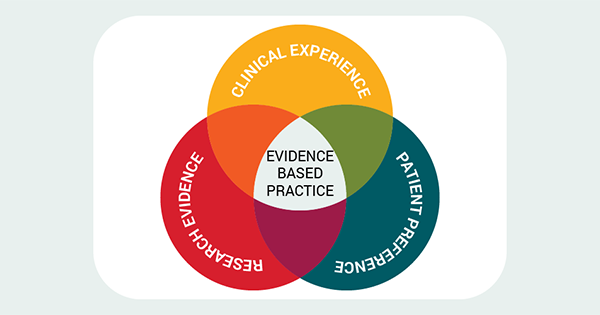

In the previous paper in this series (Ellis, 2024), we considered the nature of evidence and evidence-based practice (EBP) as it applies to healthcare and social care. We identified how EBP has a number of definitions and how, whatever the definition, it requires practitioners to interpret the evidence to meet the needs of the specific patient and the situation in front of them.

We identified that EBP is more than just the interpretation and application of research in that it requires the professional to consider issues such as patient preference, the law and ethics, as well as the availability of professional skills. In this respect EBP is a practical undertaking as much as a scientific one.

We identified how EBP is important in ensuring health and social care professionals achieve the best outcomes for patients while using resources wisely. We also identified how the application of evidence also helps protect the practitioner from potential litigation.

In this paper, we will consider the research hierarchy of evidence and what this might mean for the practice of EBP. We will also start to consider some of the barriers that get in the way of applying EBP.

Hierarchies of research evidence

While we have previously identified how EBP is an amalgam of different forms of evidence and thought processes, there is little doubt research, in its various forms, is the main basis on which decisions about practice should be based. It is worth considering, therefore, how research should be used to inform practice.

When considering a practice-related question and thinking about the sorts of research evidence which might help address it, it is important to consider two key issues: what is the nature of the question and what type(s) of research provides the best, strongest, evidence to answer it.

The first question is one about issues such as whether the question is about how people experience care or how effective care is. In the first instance, the answers might be found in research, which is qualitative (concerned with human experience) and in the second, from research, which is quantitative (concerned with measurable things) (Parahoo, 2014). This is important because as we shall see, hierarchies of evidence need interpreting in relation to the nature of the evidence being evaluated.

Hierarchies of evidence provide health and social care professionals with some idea of the sorts of research which could if it is of a good quality, provide the best evidence for them to answer the practice question facing them. It is important to stress here that while certain forms of research are identified as providing stronger evidence than others, this is the case only if the research has been properly undertaken and is of good quality. It is also only the case if the research was undertaken in situations and with participants who are broadly similar to the situation and people the practitioner is going to apply the research to.

Polit and Beck (2020) present a hierarchy of evidence [Figure 1], which is both comprehensive and recognises qualitative research. Systematic reviews provide the strongest evidence because they include more than one research study. This means the likelihood of the conclusions of the review being reached by chance is smaller than that of any single piece of research. Systematic reviews also, by virtue of drawing evidence from more than one research study, dilute out any weaknesses present in a single study’s design. Perhaps the greatest contribution of systematic reviews to an evidence base is that they apply rigid and objective criteria for the inclusion of research (Siddaway et al, 2019); that is, they assess the quality of the research they include, meaning the reader can place a certain degree of faith in their conclusions.

Systematic reviews, which include meta-analyses, use statistical data from a number of studies that they collectively reanalyse. This means that they can take data from studies that may have been quite small and combine them to get conclusions that are statistically more meaningful (Mantsiou et al, 2023). Such analyses, when done well, provide a degree of statistical assurance greater than that of any single research study.

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are considered the next highest form of evidence because of the rigour applied to their undertaking. RCTs are also considered to be very evidential because they usually recruit the participants using probability sampling, meaning that they have increased generalisability and applicability– that is, their findings apply to the whole population from which the research participants were drawn. Generalisability is incredibly useful for health and social care professionals looking for evidence to treat the patients in front of them because it provides assurances that the research applies to people who share some defined characteristics (Murad et al, 2018).

Polit and Beck’s (2020) hierarchy lists qualitative studies towards the bottom primarily because they are not generalisable, but then they do not seek to be. Qualitative studies, which seek to understand and interpret people’s experiences, provide a form of evidence that is different from that provided by quantitative studies, and so its value may not lie in generalisability, but in its depth of understanding of an issue from the point of view of people experiencing a given phenomenon (Moule, 2021). We will consider these distinctions in some detail later in this miniseries.

When considering the application of evidence in the clinical setting, it is important, therefore, that health and social care professionals have a working knowledge of what forms of evidence best apply to the question they are asking and also which forms of evidence are the strongest.

Barriers to evidence-based practice

Like all change and new ways of working or thinking, there is always a danger that barriers will emerge that prevent people from adopting or accepting what is new. In their focus group-based research, Pitsillidou et al. (2023) identified how a lack of logistical support from management, difficulties accessing research, insufficient knowledge among nurses about how to get theory into practice, nurse attitudes to change, being overworked, attitudes of managers and the inability of institutions to adopt change all stood in the way of nurses adopting evidence-based practices.

In a synthesis of qualitative evidence which drew on 33 research papers, McArthur et al. (2021) identified that the barriers facing long-term care staff in relation to applying evidence-based practice included:

- Time.

- Poor staffing levels.

- A lack of finances and other resources.

- Inadequate teamwork.

- A lack of organisational support

In a similar review of a variety of studies with a qualitative synthesis, Mathieson et al. (2019) identified how community nurses experienced a number of barriers to the implementation of innovation in their practice. These barriers are related to issues such as the structure of the organisation, the impact on the relationship with existing clients, the need for training and ongoing support, interactions with other professionals, prioritising different changes happening simultaneously, and the lack of availability of evidence and the skills to appraise it.

What is apparent from these diverse research papers is just how much influence educational, human and management factors have in relation to the adoption of evidence in all health and social care practice settings. This suggests there is an ongoing need for education and training about evidence as well as for the education and development of managers who need to develop the skills and knowledge the be able to promote and support evidence-based practices in the workplace. Finally there are also issues about making resources available for the identification and adoption of innovations at a professional as well as local level. We will discuss many of these issues in later papers in this miniseries.

Conclusion

This paper has considered the hierarchies of evidence and how they might apply to the consideration of different forms of research as part of the process of applying evidence-based practice in health and social care settings. We have identified how, while hierarchies are valuable in deliberations about which forms of research are the most important for clinical practice, health and social care professionals also need to consider the value of individual research methodologies in relation to the specific patient or clinical question they are facing.

We have also identified that all research needs to be evaluated for its quality before any clinician might choose to apply its findings where they work. Finally, we have identified some of the barriers to getting evidence into health and social care practice, identifying that most of these relate to human rather than process-related factors.

In subsequent papers in this series, we will uncover strategies for evaluating research as well as for overcoming barriers to the implementation of evidence in practice and promoting its adoption.