Venous leg ulcers (VLUs) are wounds that typically develop between the ankle and the knee, most commonly in the gaiter area [Figure 1] (National Wound Care Strategy Programme, 2023). They are primarily caused by sustained venous hypertension, which results from dysfunction in the venous system, including valvular incompetence and impaired calf muscle pump function (Atkin and Clothier, 2023). This elevated venous pressure leads to capillary leakage, tissue oedema and inflammatory changes that compromise skin integrity and delay healing (Atkin et al, 2024).

VLUs represent the most common type of lower limb ulceration, accounting for approximately 60–80% of all cases (NICE, 2024). Prevalence increases with age, and it is estimated that up to 1% of the population in developed countries will experience a VLU at some point (De Moraes Silva et al, 2024; Guest et al, 2018; NICE, 2024; Probst et al, 2023). The burden of disease is substantial, impacting patient quality of life and posing significant demands on healthcare systems due to long healing times and high recurrence rates (Guest et al, 2018).

It is acknowledged that the prevention of recurrence is often complex and multifactorial; many aspects need to be considered, including the patient’s suitability for venous intervention to treat the underlying venous incompetence (Gohel et al, 2018), the importance of maintaining a healthy weight, increased physical activity and the general promotion of healthy lifestyle behaviours (Smith et al, 2018). However, this paper will specifically focus on the evidence base, clinical effectiveness and best practice recommendations relating to the use of compression hosiery.

Role of compression in patients with VLUs

Compression therapy is the cornerstone of both the treatment and prevention of VLUs (Isoherranen et al, 2023). Its primary mechanism involves the application of external pressure to the lower limbs to counteract venous hypertension. By exerting controlled pressure, compression therapy improves venous return, reduces venous distension, reduces inflammation, improves microcirculation and enhances the function of the calf muscle pump (Atkin and Shirlow, 2014; Beidler et al, 2009). This external support reduces oedema, improves microcirculation and promotes the delivery of oxygen and nutrients to the affected tissues, facilitating wound healing (Wounds UK, 2023).

It is widely accepted that compression therapy increases the healing rates of venous ulceration. This concept has been proven through a high level of evidence, including systematic reviews (O’Meara et al, 2012). The required level of compression needed to heal patients is also generally standardised, with recommendations stating that levels of at least 40 mmHg at the ankle are needed to optimise healing (National Wound Care Strategy Programme, 2023; O’Meara et al, 2012). However, there appears to be confusion about what is the optimum level of compression needed to prevent recurrence of ulceration, and rather than clinicians considering the therapeutic dose of compression needed (Hopkins, 2023), there often appears to be a standard approach of ‘class II stockings’ without a clear understanding of the level of compression provided by various types of stockings.

Recurrence rates of venous ulceration are reported to be as high as 70% at 3 months post-healing (Franks et al, 2016). For many clinicians, it feels like common practice that there are often repeated cycles of ulceration, healing and recurrence for many patients (Atkin, 2019b). It is important to remember that venous hypertension is often a chronic condition that necessitates lifelong maintenance in the absence of venous intervention. Therefore, ensuring an appropriate level of compression is continued on a long-term basis, one that is therapeutically effective at controlling venous hypertension, is vital to prevent recurrence of ulceration.

Contraindication to compression

Prior to initiating compression therapy, clinicians must conduct a comprehensive, holistic assessment to determine the patient’s suitability for compression and to identify the most appropriate compression for that specific patient (Wounds UK, 2021). This assessment should consider a range of patient-specific factors, including the patient’s expectations and understanding of the rationale for compression therapy, mobility, dexterity, capacity to use compression as indicated, ability to apply/remove compression, allergy status and relevant lifestyle considerations (Wounds UK, 2021). Central to this process is the facilitation of shared decision-making, ensuring that patient empowerment and informed choice remain integral to care planning.

In addition, assessment of the limb is essential, taking into account limb shape and size, skin condition/integrity, severity, location and type of oedema. Crucially, assessing the patient for the presence of significant peripheral arterial disease, as this represents a direct contraindication for compression therapy (Mosti et al, 2024). A detailed patient history should therefore be obtained, including the patient’s medical history, comorbidities and current medication, assessing for risk factors for peripheral arterial disease. This should be combined with a formal arterial assessment, which may include pulse palpation, Doppler waveform assessment and arterial pressure measurement, such as ankle–brachial pressure index or toe pressure (Mosti et al, 2024; Wounds UK, 2022).

Types of compression therapy

Various compression therapy devices are available, aiming to provide the recommended 40 mmHg compression needed to heal patients with VLU. These include compression bandages, compression wrap systems and two-layer compression hosiery kits. However, once a patient is healed, there is often a consideration of ‘stepping down’ to a lower level of compression or moving from compression bandages to compression hosiery for long-term management.

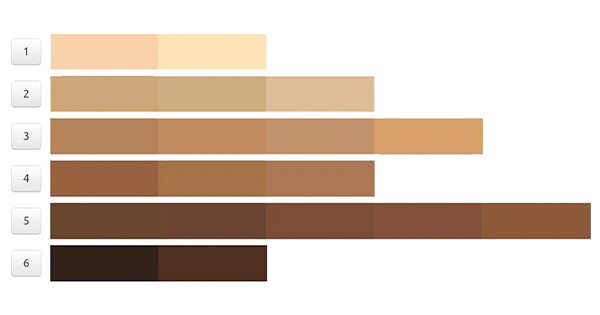

Compression hosiery comes in many different brands and types; the clinician must be aware of the dose of compression provided, and this may differ according to the strength (e.g. class 1, 2 and 3), the knit (flat knit or circular) and the classification (e.g. British or European: German [RAL] or French) [Table 1]. European classifications tend to be stronger or have a higher compression value than British standards, and are often manufactured using stiffer fabric (Atkin, 2019a). This has advantages for managing oedema, as it provides a stiff structure around the limb to prevent oedema from forming. Differences between compression strengths/classes/types can also vary according to the manufacturer/product. These nuances can make the selection of compression hosiery difficult for generalist professionals.

One of the most common barriers to compression hosiery use is discomfort (Chitambira, 2019). Poorly fitting garments can directly impact patient comfort, causing skin irritation, pain, or even pressure injuries if not correctly sized and applied (Gong et al, 2020). Therefore, clinicians’ knowledge of types, styles, ranges and differences in compression hosiery products is vital to help aid in choosing compression hosiery that is effective and comfortable to wear. Additionally, the patient’s ability to apply and remove compression needs to be considered, as accessibility can further hinder usage; many patients, particularly older adults or those with reduced dexterity, arthritis, or morbid obesity, struggle to apply and remove compression hosiery independently. In patients who find they have difficulty with donning high-compression garments, solutions need to be explored, such as compression applicator/removal (donning and doffing) aids, as without addressing these issues, it can lead to inconsistent use or complete discontinuation (Hagedoren-Meuwissen et al, 2024).

Compression hosiery kits (40 mmHg) for long‑term prevention

Compression bandages tend only to be used in the healing or intensive management stage of oedema reduction, but become unsuitable for long-term prevention due to the requirement of regular reapplication, often from a healthcare professional. Therefore, there is often a consideration of ‘stepping down’ a patient once healing/initial limb reduction has occurred. However, there may be no such requirement if the patient is being managed in ‘self-care’ solutions, e.g. compression hosiery kit, which is designed to deliver a pressure of 40 mmHg at the ankle. Compression hosiery kits are proven to be a cost-effective option compared to traditional four-layer bandages (Ashby et al, 2014), but importantly, when considering recurrence of ulceration, managing patients within the acute phase of ulceration with a compression hosiery kit reduces the risk of recurrence. The Venus IV study (Ashby et al, 2014) showed a statistically significant reduction in the risk of recurrence, with a 14% rate of recurrence in the compression hosiery (40 mmHg) group compared to 23% in the bandage group (HR 0.56, 95% CI 0.33–0.94; p=0.026). It is thought that patients who become used to wearing hosiery as an ulcer treatment would be more likely to wear it as a maintenance treatment after healing and, therefore, reduce their risk of ulcer recurrence (Ashby et al, 2014; Nelson and Bell-Syer, 2014).

Over the last two decades, there has been the emergence of compression wraps for lower limb management; the overall cost-effectiveness of these in the healing of patients with active venous ulceration is under investigation with the VenUs VI study, which is soon to be published (Arundel et al, 2023). However, the use of compression wraps in the management of oedema and lymphoedema is common practice, based on the evidence of effectiveness of oedema reduction (Damstra and Partsch, 2013; Mosti et al, 2015; Taha et al, 2024; Williams, 2016). Compression wraps are suitable for self-care as they deliver reliable compression values when self-applied (Partsch, 2019) This oedema reduction theoretically supports the use in prevention of recurrence, but due to the current lack of clear overall cost-effectiveness in prevention of recurrence of ulceration, it is considered best practice to only use compression wraps where the patient is unable to wear/use compression hosiery. This could include patients with difficulty in reaching their toes due to mobility/dexterity issues, such as morbidly obese patients or patients that find compression hosiery uncomfortable (Fletcher et al, 2024; Petkovska, 2017).

Evidence of the role of compression in the prevention of recurrence

There is a plethora of evidence on the effectiveness of compression hosiery in the prevention of recurrence (De Moraes Silva et al, 2024; Nelson and Bell-Syer, 2014), with a clear recommendation that the higher the level of compression, the more effective it is in reducing recurrence (Nelson and Bell-Syer, 2014). The most recent summary of evidence on the prevention of recurrence of ulceration was published by the Cochrane group in 2024 (De Moraes Silva et al, 2024). They concluded that class 3 compression stockings are the most effective at reducing risk of recurrence and are more effective than class 2, but acknowledge that higher compression may lead to lower concordance with recommended treatments.

Therefore, considering the need for the highest level of compression in terms of effectiveness (De Moraes Silva et al, 2024), the evidence that compression hosiery kits (40 mmHg) reduce the risk of recurrence (Ashby et al, 2014) and the fact the patient is already in a self-care solution, there is a need to change clinicians’ perspective to stop thinking about stepping down but instead continue with compression hosiery kits as a long-term prevention strategy. This strategy theoretically has many potential advantages. The patient is already familiar with the stocking; the compression liners make the application of a second stronger stocking easier; there may be no need for additional prescriptions, reducing cost; and one product being used throughout would also eliminate waste.

Patient education and shared decision‑making

Despite the proven effectiveness of compression hosiery in the prevention of recurrence, patient adherence remains a significant challenge (Bar et al, 2021; Weller et al, 2016). Multiple factors, including comfort, fit, accessibility and socioeconomic status, influence a patient’s willingness and ability to consistently use compression garments (Perry et al, 2023; Ritchie and Turner-Dobbin, 2023; Wounds UK, 2021). Weller et al (2021) further expanded factors that influence patients’ adherence to compression therapy and described these as:

- Knowledge domain (patient understanding the management plan and rationale behind treatment);

- Social influences (compression-related body image issues);

- Beliefs about consequences (understanding the consequences of not wearing compression);

- Emotions (feeling overwhelmed because it’s not getting better)

- Environmental context and resources (hot weather, discomfort when wearing compression, cost of compression);

- Beliefs about capabilities (ability to wear compression);

- Behavioural regulation (patience and persistence);

- Memory, attention and decision-making (remembering self-care instructions).

- Considering this factor will inform shared decision-making and optimise self-care (Weller et al, 2021).

The effective use of compression hosiery in the management of VLUs and prevention of recurrence relies heavily on a structured, patient-centred clinical approach. Best practice involves thorough assessment, individualised fitting, patient education, and ongoing multidisciplinary support to maximise adherence and therapeutic outcomes [Table 2]. Education should be tailored to the individual’s learning needs, with the use of demonstrations, written materials, videos, and, where possible, hands-on practice. Multilingual resources or culturally appropriate materials should be provided when needed. Clinicians must avoid terminology and labelling patients, such as ‘non-compliant’; instead, clinicians need to focus on building therapeutic relationships with their patients (Atkin, 2019b).

Conclusion

Prevention of recurrence of venous leg ulceration remains a complex and persistent challenge, characterised by high recurrence rates that can significantly impact patient wellbeing. This paper demonstrates that the prolonged use of compression hosiery is a crucial method for preventing ulcers from recurring, with substantial evidence supporting its effectiveness in reducing venous hypertension and maintaining skin integrity following healing.

However, optimal outcomes depend not only on prescribing compression but also on the correct assessment, fitting, and support to ensure continued use. Patient adherence is often compromised by discomfort, difficulty in application, and wider socioeconomic and cultural barriers. Addressing these challenges through comprehensive patient education, shared decision-making, and tailored support strategies is fundamental.

Best practice in clinical management involves a multidisciplinary, patient-centred approach that emphasises therapeutic relationships, continuity of care, and appropriate selection and monitoring of compression hosiery. Crucially, clinicians must move away from routine ‘step-down’ approaches post-healing and instead consider maintaining effective levels of compression therapy, such as compression hosiery kits delivering 40 mmHg pressure as a long-term preventive solution.