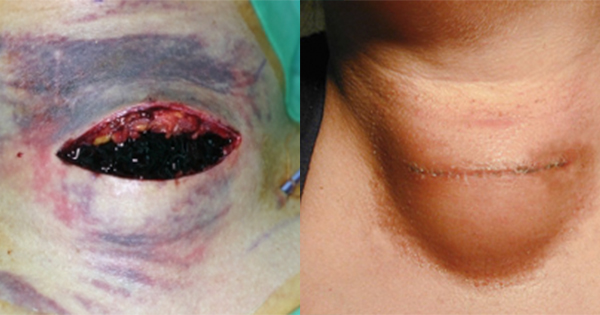

A surgical site infection (SSI) is an infectious process present at the site of surgery (Stryja et al, 2020). SSIs are the third most commonly reported type of healthcare-associated infection (HCAI; Hegarty et al, 2019) as well as the most costly (World Health Organization [WHO], 2016), representing a burden to individuals, their families/carers and health services.

If the infection becomes systemic, SSIs can be potentially life-threatening, resulting in significant patient morbidity and mortality (WHO, 2016).

Rates of inpatient SSI have been established by high-quality studies and prospective surveillance. However, incidence rates of SSI in the community are less clear. This may be due to the trend for earlier hospital discharge, or lack of reporting and documentation (Public Health England [PHE], 2019). Under-reporting, or reporting of composite endpoints such as ‘wound complications’ or ‘surgical site incidences’ (e.g. wound breakdown, seroma, haematoma), means that post-surgical complications may not be captured in hospital-based surveillance studies, particularly if infections are relatively minor and are not reported by the patient to their GP, or by the GP to the surgical team. Therefore, the true cost of SSIs to the patient, family and organisation may be grossly underestimated in the community (Oliveira et al, 2007).

Research suggests that standardised education is lacking for clinicians involved in dressing surgical wounds (Eskes et al, 2014). It is estimated that nearly 50% of SSIs could be prevented by following evidence-based guidelines (Meeks et al, 2011; Center for Disease Control, 2016).

This document focuses on postoperative strategies specifically aiming to prevent SSI, rather than other surgical site incidences or complications.