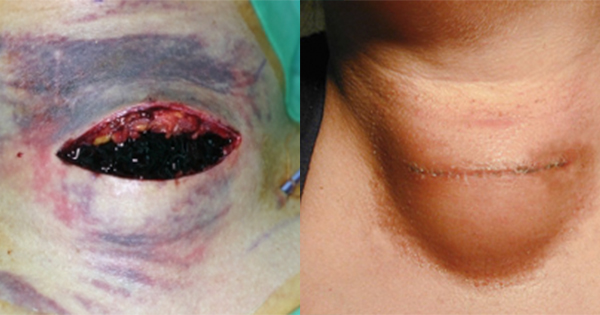

Within the UK, one in every fourth baby is delivered by CS (National Health Service [NHS], 2023a). Although considered to be the most common and safe surgery in women, complications are well documented (National Library of Medicine [NLM], 2024), including surgical site infection (SSI). Stryja et al (2020) define SSI as an infectious process present at the site of surgery.

Clinical signs and symptoms of wound infection include heat, redness, swelling, elevated body temperature and purulent wound exudate (International Wound Infection Institute [IWII], 2022). Despite efforts made during modern surgical procedures, SSI after CS continues to rise. A systematic review and meta-analysis revealed that SSI incidence varied between countries, the highest being in Africa and lowest in North America (Farid Mojtahedi et al, 2023).

Risk factors and comorbidities associated with SSI in CS wounds

Maternal obesity triples the risk of developing wound complications including SSI and associated morbidity (delayed recovery, increased discomfort and a reduced quality of life [QoL]) (Berríos-Torres et al, 2017; Dias et al, 2019). Childs et al (2020) note the growing epidemic of obesity in women of reproductive age increases the risk of SSI, in particular among morbidly obese women (body mass index [BMI] ≥40 kg/m2), in whom the SSI rate can reach 50% (Anderson et al, 2013; Yeeles et al, 2014).

Several factors play a crucial role in SSI risk, including hypertension, duration of labour, rupture of membranes, type of anaesthesia, quality of post-operative care, early mobility and obesity (BMI >30 kg/m2); gestational diabetes and pre-existing type 1 diabetes also increase the risk of SSI (Wloch et al, 2012; Childs et al, 2020; Gomaa et al, 2021; Erritty et al, 2023). In a study of 1,682 women who received either elective or emergency CS, raised BMI (≥35 kg/m2), smoking history and emergency CS were found to be independent risk factors for post-CS SSI (Erritty et al, 2023). Stress, nutritional status, certain medications and alcoholism potentially slow the speed of healing of a CS wound (NLM, 2023; NHS, 2025).

SSI can lead to a significant cost burden for healthcare systems (Childs et al, 2020; Angolile et al, 2023), as well as maternal and family distress, problems with bonding and slow recovery for the mother (Childs et al, 2020). If the surgical wound becomes infected, there are increased demands on NHS resources (e.g. higher workload for general practitioners [GPs] and midwives, and increased district nurse visits), for medication (e.g. antibiotics and pain management) and increased dressing changes (Childs et al, 2020; Stanirowski et al, 2016).

For some patients, re-admission for surgical revision and management of the wound may be necessary. In addition to the emotional and physical pain for the mother, an infected CS wound leads to an estimated 4 days of hospitalisation and an additional cost of £3,173 per patient (Stanirowski et al, 2016). Proactive SSI prevention, based on patient risk identification, should be an integral part of pre-, intra- and post-operative CS wound care.

Pre-operative management

There is significant evidence for the use of prophylactic antimicrobial agents to prevent SSIs in CS wounds (Childs et al, 2020). Measures to prevent SSIs include nasal decolonisation, effective skin preparation using an antiseptic preparation and management of co-morbidities. Hair removal (using clippers) should only be undertaken to facilitate surgery or for applying adhesive dressings (Mangram et al, 1999; Tanner et al, 2011; Tanner and Melen, 2021). Dhamnaskar et al (2022) suggest that pre-surgical hair-shaving should be avoided in people undergoing clean-contaminated surgery or a surgery lasting less than 2 hours; this may reduce the risk of SSIs in these patient groups.

Before surgery, preparing the skin with antiseptic agents has been shown to reduce risk of infections (Al Maqbali, 2013). Contamination with Staphylococcus aureus – the source of approximately 40% of all SSIs in CS wounds – can be reduced with the use of a body wash (Wloch et al, 2012; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE], 2024).

Evidence supports the effectiveness of pre-operative decontamination with octenidine-based antimicrobial products: Jeans et al (2018) reported a 3-fold reduction in methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) infection rate after employing a 5-day decontamination routine with octenisan® wash lotion – this is a mild and gentle cleanser, suitable for all skin and hair types, and provides a soap-free alternative, with a neutral skin pH value. It can be used for decontamination of skin prior to hospital admission for CS or, in the case of emergency CS, can be used immediately before transfer to theatre. Post-surgery, it can be used for whole-body washing providing the lotion is used on intact skin only. For cleansing of wounds, including infected wounds, octenilin® irrigation solution can be used.

For immobile patients, or those with limited mobility, octenisan® wash mitts can be used for post-operative cleansing and decontamination. They are ideal for cleansing and decontaminating between skin folds.

Intra-operative precautions

Intra-operatively, local and national guidance to prevent SSI should be adhered to (De Simone et al, 2020):

- Skin-cleansing protocols aligned with local guidelines

- Hair removal using clippers (if considered necessary)

- Ensuring intra-operative normothermia

- Antimicrobial prophylaxis and administration (if needed)

- Sterile instruments

- Timely primary incision closure.

Post-operative management

Within the UK, many women are discharged to community care approximately 24 hours post-CS (Childs et al, 2020). Any suspected SSI in the community will require care from the GP, community midwives and nurses. If infection is suspected based on clinical signs and symptoms, antibiotics are prescribed, but in an era of antibiotic resistance, every effort needs to be made to offset antibiotic prescribing unless clearly indicated (Childs et al, 2019).

Practical tips for preventing SSI in CS wounds

Antimicrobials in acute care

From pre-surgery skin decontamination to post-discharge wound care, optimal prevention and decolonisation along the patient journey can help reduce the risk of SSI and improve healing outcomes (Calderwood et al, 2023).

Antimicrobials in community care

Since most women are discharged to the community settings within 24-48 hours (NHS, 2023b), it is important for clinicians to proactively plan for CS wound care in community settings. This will ensure early identification of a suspected SSI and early appropriate interventions.

A 12-month evaluation of octenidine-containing wash mitts and their effect on preventing SSIs demonstrated a reduction in the prescribing of antibiotics, improvements in the patients’ QoL (as patients were able to use them if they were unable to shower or bathe) and no report of Pseudomonas infections (Dhoonmoon and Dyer, 2020).

Using octenidine-containing products in practice

Octenidine-containing products are antimicrobial solutions used for cleansing; they are an antiseptic with a low risk of antimicrobial resistance (Kramer et al, 2018; Haesler, 2020).

Figure 1 provides an algorithm on practical tips for wound cleansing, depicting how this product range can be used in routine clinical practice.

Clinicians have numerous wound dressings available. It is important to ensure dressing choice is evidence-based. WHO guidelines for SSI prevention emphasise the importance of ‘not using any type of advanced dressing over a standard dressing on primarily closed surgical wounds for the purpose of preventing SSI’ (WHO, 2016).

Appropriate dressings should be individualised based on patient needs (e.g. the healing stage and risk factors; Childs et al, 2020). Appropriate individual assessment of each patient is key to ensure that optimal healing can be achieved. To ensure care continuity when the patient is moved to community from hospital, a well-documented care plan should be in place to ensure shared, optimal care (Childs et al, 2020).

Wound dressing choices for CS wounds

A dressing appropriate for CS wounds performs the following functions (Childs et al, 2020):

- Protection of the incision

- Prevention of contamination

- Provision of both a healing environment and patient comfort.

Determining risk for SSI prevention in CS wounds

In combination with the pre-, intra- and post-operative SSI prevention measures, the suggested pathway shown in Figure 2 provides practical tips for clinicians to adapt their SSI prevention approach.