Surgical site infection (SSI) is globally recognised as a SWC, and there are both national and international guidelines available for the prevention of SSI (World Health Organization [WHO], 2018; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE], 2019a). In the United Kingdom (UK), surveillance of SSI is both mandated and voluntary according to surgical specialty (UK Health Security Agency, 2022). This has helped to drive focus on evidence-based interventions throughout the patient’s surgical journey to help reduce the likelihood of SSI. SWD is a serious post-operative complication that may or may not be associated with SSI. Despite the negative effects on patients, clinicians and the wider community (Sandy-Hodgetts et al, 2013), its prevalence and impact are underreported (Morgan-Jones et al, 2023). SWD delays healing, adjuvant treatment and hospital discharge, and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality, readmission, further surgery, suboptimal aesthetic outcome and impaired psychosocial wellbeing (Sandy-Hodgetts et al, 2016; 2020; World Union of Wound Healing Societies [WUWHS], 2018). Furthermore, evidence shows that SWD is increasingly likely to occur in the community, and for most patients, dehiscence occurs following discharge from hospital (Sandy-Hodgetts et al, 2016; Hughes et al, 2021). A study in the UK found that more than half (57.1%) of wounds due to SWD healing by secondary intention were being cared for in the community, rather than in a primary or secondary setting (Chetter et al, 2017).

Background to the consensus document

Raising awareness and improving identification, prevention and management of SWD may help to prevent patient distress, free up clinician time and save on associated costs. The consensus document (Morgan-Jones et al, 2023) provides practical guidance on how to improve prevention, identification and management of SWD, with the aim to improve outcomes for patients. Within the consensus document, the expert group emphasise the importance of consistent care and standardisation across surgical settings, as well as the need to take a patient-centred approach that encompasses the patient’s entire surgical journey.

Assessing risk

The fundamental premise of pre-operative risk assessment is to consider each individual patient’s unique circumstances and characteristics (Sandy-Hodgetts et al, 2023). Where possible, optimisation pre-surgery is vital. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) guidance is now available and provides surgery-specific, evidence-based and patient-centred recommendations that can support postoperative recovery and reduce SWCs (ERAS Society, 2023). For elective surgeries, robust and often surgery-specific prognostic tools can be used to identify whether surgery would lead to an unacceptably high risk of SSI. This may provide a rationale for delaying or postponing surgery until such time that patient-related modifiable risk factors (e.g. comorbidities or lifestyle issues) have been addressed, where possible, to reduce the likely risk of SWD.

Box 2 lists the intrinsic (patient-related) and extrinsic (procedure-related) risk factors for SWD. Where surgery is planned, pre-operative consultations provide an opportunity for risk assessment that can be used to discuss risks and potential outcomes with the patient, to introduce a patient-centred plan to address patient-related modifiable risk factors (WUWHS, 2018). Risk assessment and planning needs to be integrated throughout all stages of the surgical journey, as risk factors can be identified at pre-operative assessment, in the operating room and postoperatively (Sandy-Hodgetts et al, 2020).

Early prevention strategies

Prevention of SSI, SWC and SWD comprises reduction of risk by following national guidelines for pre-, peri- and postoperative care (WHO, 2018; NICE, 2019a; National Wound Care Strategy Programme [NWCSP], 2021; ERAS Society, 2023), educating patients about risk, prioritising infection prevention measures, improving interdisciplinary working, and promoting excellence in surgical practice and technique.

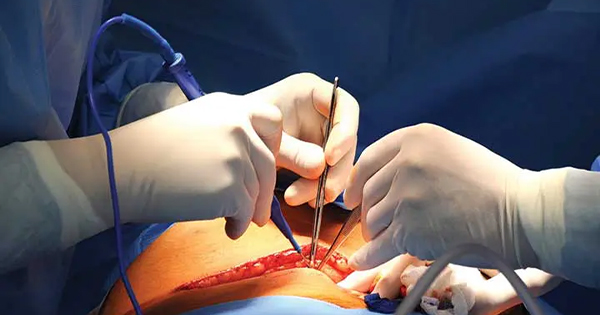

SWD is not always as a result of SSI and can be due to disrupted healing, mechanical stress and surgical technique. For example, SWD can arise due to failed closure of the skin and deeper layers, trauma, coughing/vomiting, haematoma/seroma, poor surgical site support, exertion and oedema (WUWHS, 2018; Morgan-Jones et al, 2023). Recognising and identifying these risks pre-and postoperatively provides an opportunity for early intervention such as the provision of anti-emetics (Gustafsson et al, 2019) and patient education. If considered appropriate, negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) can also be used at the prevention stage; for example, NICE recommends that PICO™ single-use NPWT (sNPWT; Smith+Nephew) should be considered as an option for closed surgical incisions in people who are at high risk of developing surgical site infections (NICE, 2019b). Good closure technique by surgeons and surgical assistants (Blencowe et al, 2019) – including use of triclosan-coated sutures (NICE, 2019a) and barbed filaments to minimise the need for irritant knots both deep and superficially – may also have the potential to reduce SWCs (Gowri and King, 2023).

Patient education plays a key role in the prevention of SWD. Clinicians need to provide information to patients regarding their surgery type and the associated risks, what they can do to optimise their condition pre-operatively, during and postoperatively, including advice regarding rehabilitation (Gustafsson et al, 2019), how to avoid undue stress to the site, how to protect the site when needed and the need to wear devices such as bras and corsets that might offer additional support to the surgical site (WUWHS, 2018; Morgan-Jones et al, 2023). Patients need to understand how to identify problems with wound healing by knowing what signs and symptoms to look out for, how and when to seek help from a professional, how to contact the clinician and how to care for their wound (e.g. how to change dressings, take care of stitches, and bathe and shower safely). This information can be provided in the form of verbal communication and demonstrations during visits, in addition to leaflets and information packs that patients can take home with them. It is paramount that all education is tailored to the patient’s needs, and the clinician should encourage the patient to ask questions to check their understanding.

The consensus document also identified a need to improve coordination between the surgical provider and community teams, since evidence shows that surgical wounds are often cared for in the community by practice and community nurses (Chetter et al, 2017). There was a consensus from the expert group that surgical and community teams should establish clear communication channels to facilitate collaboration and coordination of care. Interventions such as shared electronic patient records, standardised protocols, and joint meetings to discuss complex cases and share best practice, can address discrepancies in care and provide education/fill gaps in knowledge. Virtual consultations and implementation of patient-submitted wound images post-discharge can also facilitate early recognition and, therefore, early intervention of SWD (NWCSP, 2021).

It goes without saying that strict infection prevention and control measures need to be followed by the patient, their carers and clinicians involved in their care. This can further reduce likelihood of wound infection from cross contamination, thereby avoiding further hospital stays, which may expose patients to the risk of hospital-acquired infection (Andersen, 2018). Antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) must be considered at all times with antibiotics being prescribed on a case-by-case basis with consideration given to optimal selection, dosage and duration of the treatment (Gerding, 2001). Current AMS strategies to reduce unnecessary antimicrobial use in wound management include accurate identification of wound infection and simple infection prevention strategies (e.g. good hand hygiene, waste management, comprehensive documentation and management of the patient environment; Wounds UK, 2020).

The initial assessment

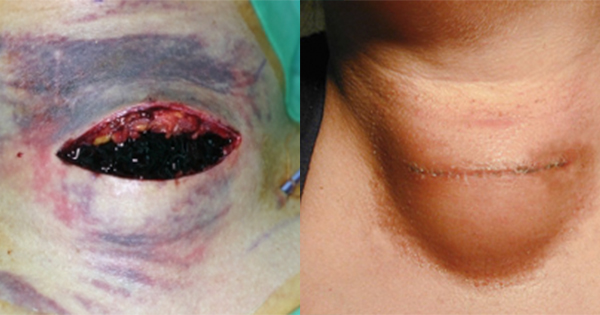

A key take-home message from the consensus document is that if wound breakdown is identified or recognised early, outcomes can be improved. Therefore, a holistic, comprehensive assessment that includes skin inspection [Box 3], medical and surgical history, nature of the surgical procedure, current health, lifestyle, current medication, pain levels and psychological status (WUWHS, 2018) is essential to assess risk and identify SWCs at the earliest possible stage, to prevent escalation into a more serious issue. Box 4 contains a list of questions that can be useful to consider when undertaking a skin assessment, particularly in those with dark skin tones where erythema associated with infection may not be readily visible (Wounds UK, 2021).

Identifying infection

Dehisced incisions may, or may not, display clinical signs and symptoms of infection, and the patient’s treatment pathway will depend on whether the incision site is infected (Sandy-Hodgetts et al, 2013; WUWHS, 2018). In the first few days following surgery, signs of inflammation — e.g. warmth, erythema, oedema, discolouration and pain — are normal and do not necessarily indicate an issue with wound healing (International Wound Infection Institute [IWII], 2022). However, if signs of inflammation extend or develop beyond this time, this may be indicative of a wound infection. Therefore, consistent monitoring is essential and where local/overt infection is suspected, topical antimicrobials should be utilised if considered appropriate — e.g. dressings with antimicrobials such as ACTICOAT™ Flex 3 (Smith+Nephew) in line with local infection management protocols. If the infection is spreading/systemic, clinicians should consider whether antibiotics are needed. Clinicians should refer to the IWII (2022) guidelines for further guidance on preventing, identifying and managing wound infection.

Use of NPWT for prevention of SWD post-surgery

For patients at increased risk of SWD, clinicians may consider using NPWT prophylactically to improve healing and reduce the risk of SWD. There is growing evidence that prophylactic NPWT, including sNPWT, is increasingly being used on closed incisional wounds to prevent SWCs (De Vries et al, 2016; Norman et al, 2020), and wounds healing by secondary intention (e.g. non-healing or infected wounds; Dumville et al, 2015). The use of sNPWT over closed surgical incisions has been shown to reduce rates of SSI, seroma and dehiscence, with an additional benefit that it may improve scar quality (Hyldig et al, 2016; Strugala and Martin, 2017; NICE, 2019b; Saunders et al, 2021). Research shows that prophylactic NPWT may also influence the tissues surrounding the incision by reducing oedema and levels of inflammatory markers (Eisenhardt et al, 2012). Use of sNPWT as an early intervention for management of SWD will be covered in a later part of this series of articles.

For further information about the consensus document and its contents, see Box 5.

Conclusion

Early risk assessment and prevention are key to optimise patients before surgery and during all stages of the surgical journey, to enhance

recovery and prevent complications, such as SWD, from escalating and deteriorating. The consensus document on prevention, identification and management of surgical wound dehiscence (SWD) raises awareness on the importance of early identification of SWD with timely and appropriate intervention. The guidance aims to potentially help reduce patient distress, free up clinician time and save on associated costs, to ultimately improve quality of care and deliver better outcomes for patients.