Wound care in the UK is a well-established financial burden costing the National Health Service (NHS) £8.3 billion annually (Guest et al, 2020), £5.6 billion of which is associated with managing unhealed wounds. This cost continues to steadily increase alongside a 71% rise in chronic wound prevalence (Guest et al, 2020). With 81% of the UK’s wound care cost incurring in the community (Guest et al, 2020), the importance of this setting cannot be overstated.

Concurrent with cost of care, providing quality wound care in the community setting has become increasingly challenging. In recent years, the number of district nurses has fallen by 43% (Fanning, 2019) despite an alarming 399% rise in community nurse recorded visits (Guest et al, 2020). Community staff shortages, alongside an increase in earlier hospital discharge (Morris, 2023), reduced access to general practitioner (GP) services and an increasingly aged population (Office of National Statistics, 2020) has had a significant impact on the provision of care. As Brennan (2020) highlights: ‘the increase in number and complexity of patients discharged from hospital means district nurses cannot get to it all’.

When community nursing services are stretched, with high complexity of patient needs, there is a need to triage and prioritise workload. The negative impact this has on the provision of wound care can be significant. Aged patients requiring wound treatment in residential homes may be seen as lower priority due to access to on-site care. However, as a wound’s status can deteriorate rapidly if not promptly addressed and appropriately managed, these patients remain at high-risk of wound complication due to their general health, mobility level and poor skin integrity (Stephen-Haynes, 2020).

Strategy for Improvement

In line with these national challenges, West Suffolk NHS Foundation Trust identified a need for improvement in wound care in nursing and residential homes. This corresponded with a Trust-wide aim to reduce same-day community nursing and out-of-hours home visits for new and existing wounds due to local workload pressures.

A resulting review of care by the tissue viability nurse (TVN) in early 2023 identified an urgent need within residential homes to improve interim wound care. In the absence of a structured, unified approach to care with readily available wound dressings, residential care homes were reluctant to provide basic wound care.

The Interim Dressing Kit Quality Improvement Project (IDK QIP) was proposed to make residential care homes self-sufficient with the provision of interim wound care. The primary goal was to improve patient safety and wound care outcomes, with a secondary aim to reduce the total number of calls made to community nurses, out-of-hour clinicians and the ambulance service for interim wound care guidance. Subsequently, routine community nurse visits could then be planned in an appropriate and timely manner to ensure patients were reviewed once the immediate care need was addressed.

Project design

Quality improvement projects (QIPs) aim to positively influence patient care by improving safety and experience of care. They typically involve small incremental changes, the impact of which is measured at frequent intervals. They employ a systematic approach in their design (Jones et al, 2019).

Taylor et al (2014) highlight how QIPs can be supported by a process for testing change ideas using plan, do, study, act (PDSA) cycles. Using this structured approach allowed the TVN to successfully manage all aspects of the IDK QIP alongside detailed process mapping to create focus and efficiency. The IDK QIP process was sub-divided into four easy-to-manage areas: communication, logistics, training and measurement, and sustainability, as detailed in Figure 1.

Plan

District nursing teams were electronically surveyed, 100% of those surveyed reported they were called out frequently to replace an existing dressing and/or called out frequently for a same-day skin tear management or similar when at full capacity. Consensus of the TVN and community teams concluded that residential care staff could manage these wounds safely with educational support and dressing provision. Subsequently, all care homes (n=33) were surveyed electronically to gauge their receptivity of an IDK. Key findings from this survey are shown in Figure 2.

Ninety-three percent of surveyed homes said that they would find helpful a step-by-step wound care guide with Quick Response (QR) codes to access ‘how to’ videos helpful; 93% felt that on-site access to an IDK would improve their patient care/safety; 100% indicated that they were happy to implement the new initiative.

Do

Upon review of the feedback received, the IDK was developed and circulated among all residential homes. The IDK included dressings and guides to enable safe and effective interim wound care while awaiting a community nurse visit. Emails detailing the launch were sent to residential homes, community nursing teams, out-of-hours services and the care coordination centre responsible for triaging visits. A written piece detailing the project was included in the Trust’s communication sheet.

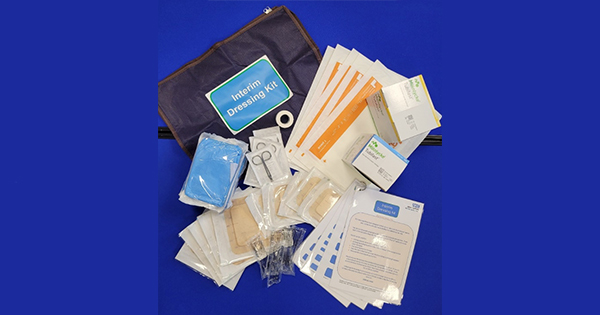

Wound dressings were selected from the wound care formulary by the TVN and listed generically, e.g. silicone foam adhesive. Industry was accessed to provide bags for the kits and any printing required. The kits did not contain any product promotion or bias. The IDKs [Figure 3] included:

- Dressing packs

- Saline 0.9% irrigation solution

- Sterile disposable scissors

- Medical adhesive tape

- Silicone adhesive foam dressing (10x10cm)

- Silicone adhesive foam dressing (15×17.5cm)

- Superabsorbent wound pad

- Tubular retention bandage (blue line)

- Tubular retention bandage (yellow line).

The IDKs included simple guides [Figure 4] with a step-by-step process for dressing a new or existing wound. QR codes linked to a relevant simple “how to’” video guided residential home staff through the process of dressing the specific wound types and using the dressings provided safely.

Guides and kits were indicated for use with:

- Existing wounds where a dressing had fallen off

- Existing leg bandaging with exudate strikethrough to outer dressings

- New weeping areas on the legs

- New skin tears, no larger than the adhesive dressings supplied

- New wounds including pressure ulcers.

Following use of the IDK, residential home staff referred the patient to the local community nursing team via their usual referral process for review by a qualified clinician. Care homes nominated an individual to stock-take the kit each week. Necessary items were replenished by the community nursing teams in line with a stock level sheet included in the kit.

Study

During initial implementation of the IDK project, most avenues of communication were used, including digital tools. However, upon reflection, it was understood that staff and service pressures made access to and acknowledgement of communication challenging. Communication and promotional needs of the IDK project had been underestimated.

Some nursing staff within the community were not aware of the IDKs for the first few months of implementation. Frequent changes in residential home managers and staff proved detrimental. Information was not always passed on from predecessors or other staff members included in the initial cohort.

Act

To improve upon this, a second drive was made to promote the awareness of the IDKs. Posters were sent to community nurse bases to raise the awareness of the kits. Face-to-face visits were made by the TVN to community nursing teams and further visits were provided to support residential homes with introduction to or ongoing use of the kits.

At the 6-month mark, further visits were undertaken by the TVN to collect feedback and monitor appropriate use of the kits. Most homes were fully utilising the IDKs at this point, however, a few were still unaware of their distribution. This was rectified by further promotion and support to encourage a greater uptake of the IDKs.

On initial distribution, a form was included in the IDK for staff to complete whenever a dressing was used. Although completion of these forms was inconsistent, they did highlight that, in some homes, using the kit for new wounds was more prevalent than for existing wounds.

A follow-up digital survey at 6 months was sent to the community nursing teams and residential homes which showed 77% of care homes had utilised the kit and 100% agreed that:

- same-day community nurse visits had reduced

- they felt confident using the kit

- patient safety had improved

- they would like the kit to remain available.

On interview by the TVN with the community nurse and residential home teams, it was agreed that the IDKs had helped to improve patient care and had reduced the number of community nursing service call-outs [Figure 5].

Out-of-hours services verbally reported a reduction in call-outs for wound care in residential homes. At 8 months, 100% of residential homes were using the IDKs.

Discussion

The concept of IDKs is not new to community practice. Skin tear boxes are regularly used in many care settings to provide immediate appropriate care (LeBlanc et al, 2018). Furthermore, Clarkson (2007) detailed a ‘dressing remedies protocol’ that was designed to provide timely and effective evidence–based wound care to newly found wounds in nursing homes. Approved dressings were available for purchase over the counter via pharmacies and kept on-site, instead of using the slower prescription route. Education was provided alongside posters with support material. Clarkson (2007) also predicted that changing practice and improving skills/knowledge within the nursing home environment should have a cost reduction benefit due to the improvement in patient outcomes. Dressings available for use by the nursing homes were limited to a selection of silicone-bordered foams.

More recently, McKay (2023) highlighted a community-led project detailing the dissemination of ‘Basic Wound Care Boxes’ during the COVID-19 pandemic. These boxes contained essential equipment required for managing skin tears and straightforward wounds, and included dressing packs, silicone dressings and irrigation solution. Relevant wound care guidance alongside pathways and dressing information was provided. A Skin Integrity team delivered training on how to undertake appropriate care of straightforward wounds (such as skin tears, minor cuts and abrasions) to improve patient safety. The aim was to reduce the number of health care professional visits. The resulting improvements in basic wound management and reduction in ambulance/community nurse call-outs led to a post-COVID continuation of the project. It was highlighted by NHS England that the project had the potential to help avoid unnecessary hospital admissions and Accident and Emergency attendance by care home residents.

The West Suffolk Interim Dressing Kit Project builds upon these previous initiatives to provide an easy-to-access kit with wide-ranging clinical indications. Brindle and Farmer (2019) identify how a well-chosen dressing can reduce the risk of contamination, reduce the risk of infection, deliver cost savings, and reduce clinician time. Selecting an appropriate dressing is vital to optimise the wound healing environment (LeBlanc et al, 2018). The dressings chosen as part of the IDKs were included to manage exudate, reduce infection risk, provide moist wound healing, and manage patient comfort. The indications for use were broad, with kit contents including padding for leaky legs, tubular retention bandages, and superabsorbent dressings in addition to the bordered silicone dressings and saline solutions used in previous initiatives.

The Interim Dressing Kits kept within each residential home allowed immediate access to dressings without delay of supply. The Trust’s utilisation of delivery of consumables to the community nurse bases, via NHS Supply Chain, allowed the community nurses to re-stock without the need for prescription or purchase at a local pharmacy, ensuring quick and continuous access to the dressings.

Differentiating this project, and fundamental to its success, was the utilisation of modern technology in the form of QR Codes [Figure 3]. These were used to provide basic wound care education, in the form of short video guides, to large numbers of residential care home staff, focusing on the interim care required at the correct educational level for non-registered carers.

The use of videos can increase a learners’ performance (Kay et al, 2012). Videos focus attention, efficiently present information, simplify complex concepts, and evoke emotional responses, which contribute to better retention of learned information (Hurtubise et al, 2013). Using QR codes to access videos offers easy and fast recognition of information sources allowing flexibility to the audience. QR codes are widely used in healthcare (Sharara and Radia, 2022), increasingly so since their revival during

the COVID-19 pandemic. A review by Karia et al (2019), however, highlights some important considerations and challenges associated with the use of QR codes in healthcare education, particularly in a clinical setting. They suggest that consideration needs to be given to the governance of introducing a QR code solution into a healthcare education setting. During the IDK project, this process was managed within local trust guidelines and, in the essence of safety, the TVN liaised closely with the Trust’s communications team when drawing up and disseminating these videos via the QR Code route.

Karia et al (2019) also stress that it is important to advise clinicians on appropriate use of smartphones to scan QR codes in the clinical environment. Use of smartphones to scan QR codes could be perceived as unprofessional by some patients in an older patient population unused to the technology used regularly by a younger generation. Therefore, it is important that patients are informed that smartphones are being used to support teaching (Karia et al, 2019).

This easily accessible form of education allowed efficient implementation of the identified improvements to care, expediting the project roll out. Using the videos as an educational tool allowed the TVN to reach a wide audience without the need for hours of face-to-face educational sessions. The QR codes, easily scanned at the time the care was provided, gave the residential care staff direct access to expert advice to enable provision of good standards of care at the point of need.

Conclusion

Challenges in the modern NHS cannot be underestimated. Workforce pressures alongside an increasing demand for healthcare requires creative adaptation to services. This QIP highlights what can be achieved through clear baseline investigation of a clinical issue, use of modern technology and by following a structured process. The TVN’s aims to ensure the maintenance of patient safety in relation to interim wound care in residential homes were met alongside a resulting positive reduction of same-day and out-of-hours community nurse visits.

Future evolution of the kit may include the addition of new dressings to expand on the use of the IDK with products to improve skin integrity, e.g. barrier products and emollients, creating a robust tool kit for a wider range of interim wound care issues. This, alongside planned expansion of the IDKs into other services such as the virtual ward initiative, and the potential to replicate in the patient’s own home, supported by home carers, will enable the TVN to continue to improve interim wound care services.