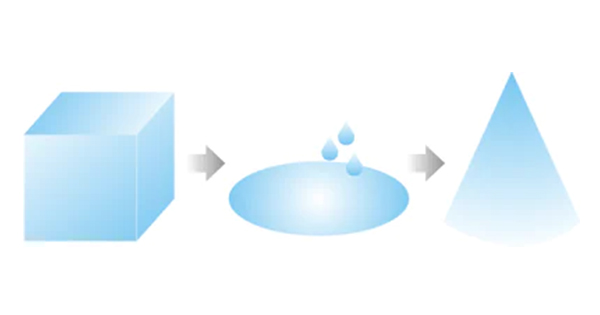

In the first paper in this miniseries about using Lewin’s (1951) unfreeze-change-refreeze model, for managing change, we identified that the model is popular with managers because of its simplicity (Ellis, 2023). We saw that the idea of unfreezing is clever because in trying to change something in the workplace, the manager needs to get the team to relinquish old ways of working and become more fluid in their thinking and behaviours so that they can, as a team, remould to the change. This is less traumatic and more long-lasting than chipping away at outdated practices or ways of thinking.

We identified that unfreezing the team requires the manager to share the vision of what it is they want to achieve. We saw that people involved in giving up old ways of working go through transitions and may have to leave their comfort zone. We identified that fundamental to achieving this is good communication and the use of emotional intelligence on the part of the manager.

Resistance to change

During this stage of the process members of the team start to understand the purpose of the change that is underway. Some people will embrace the change and want to get on with it because they see the value in it. Others will be ambivalent and a third group will want to resist the change and start throwing up barriers, which the manager will need to address.

This third group, those resisting change will do so for a number of reasons:

- Anger at being told what they already do is not good enough

- Loss of control over ways of working

- Uncertainty about the usefulness or purpose of the change

- Fear of losing face because they understand the old way of working very well

- Fear of becoming incompetent or redundant in the new system

- Excuses that the change will take too much time, which they have not got

- Dislike of the people who are running the change

- Fear of the motivations for the change.

- Poor communication

- Previous bad experiences of poorly managed change (Mareš, 2018).

When people create these barriers and obstacles to change, it is difficult for the manager to handle unless they commit time and effort to support the staff team. Alvesson and Sveningsson (2016) make the very real observation that much change, and the literature about change is manager centric. This means that the staff group feel disempowered and removed from the processes of decision making. Getting to grips with this requires a change in the culture of many organisations. This includes some of the decision making about a change needing to be driven with a view to the shared values of the team as well as with a view to the personal identities, and reshaping of team identities, which is a by-product of change (Alvesson and Sveningsson, 2016).

Some of the simple strategies to help address the resistance to change include:

- Getting staff involved in choices and decision making about the change

- Creating champions among the staff team who play a role in framing and shaping the change

- Communicate, communicate and communicate again

- Be aware of staff who are struggling with the change and give them support

- Be prepared to adapt if the change is not working (Ellis, 2022).

Of course there is no guarantee these strategies will always work, so it is wise that any manager leading a change process ensures they have allies in the team to support the process as well as support elsewhere to allow them to offload their own stress if they need.

Emotional responses to change

It is a simple fact of life that change is stressful. The famous Holmes-Rahe Social Readjustment Rating Scale (1967) identifies how even changes which people want and which they pursue can be stressful, e.g. starting a new job, moving home and getting married. How much more so will change that people do not want cause them stress?

The stress of change is linked to what Bridges and Bridges (2019) call transition. According the Bridges and Bridges (2019) change is situational while transition is psychological. By this they mean that things, processes, ways of working can change, while people have to go through a psychological period of transition. These transitions occur differently for different people and require that staff reorientate themselves to what is going on. A failure of the manager to support people to undertake transition will mean that the furniture is rearranged but people have not come on the journey, so the culture of the team has stayed the same.

Hopson and Adams (1976) created a now famous, and very useful, model regarding ‘changes in self-esteem that occur during a transition’. This model identifies the psychological responses people might have when going through a period of transition associated with a change. The stages of the model are described as:

- Immobilisation: when people experience this they are unable to act. They are feeling overwhelmed, unready for the change and are experiencing fear

- Minimisation: when experiencing this, people pretend the change is not happening. This coping mechanism, essentially denial, often occurs when a change is not planned and people are experiencing the change as a crisis

- Depression: this stage is as it sounds and occurs as a response to what people involved fear they might be losing as a result of the change

- Accepting reality: at this stage of transition people are starting to accept that the old ways of working are going and the new ways are the new reality

- Testing: when staff get to this stage they start to try the new ways of working and experiment with the new change to see what works for them

- Seeking meaning: this is essentially a reflective stage during which staff seek meaning in the change. They seek to understand what has changed and how this fits into their view of the world and the things they already know and do

- Internalisation: this stage of transition occurs late in the process when people have tried and reflected on the change and started to adopt it as their ‘new normal’.

This model does not apply to everyone, in fact few people experience all of the stages. Hopson and Adams (1976) identify that people:

- Can move in either direction through the model

- Experience the same stage more than once

- Move at different rates though the stages

- Skip some stages.

Within the team, different people will be at different stages at different times. This means the manager or leader needs to know their team, read the signs and direct their attention and support accordingly.

Overcoming the emotional response to change

There is little doubt that people in health and social care leading change need to exercise emotional intelligence to do so (Goleman, 2020). This means being attuned to the emotional language and behaviours used by staff that express how they feel about the impact of the change on them at a point in time.

There is little doubt that managers who are met with emotional resistance to change need to exercise an even more powerful set of emotions to overcome this. This will mean a different approach and different strategies for different members of staff.

Conclusion

In this paper we have seen that the second stage of the Lewin unfreeze-change-refreeze model for managing change can be challenging. We have identified that people resit change for a number of reasons, not all of which are reasonable. We have seen that the manager will have to use a number of strategies for overcoming the resistance to change and that the manager should also ensure they have support both for the change and themselves in order to be successful.

We have identified that people will have psychological responses to change, even change they want. We have also seen psychological transitions through change can be complex and vary widely between individuals. Furthermore, managers need to be aware of this and use different strategies to support different staff as they make their individual transitions.

In the next paper in this mini-series we will look at the process of refreezing once a change has been made. We will explore in some more detail the skills a manager may need to apply when supporting staff through change and into a period of acceptance and normalisation of a change.